By Ngozi Nwoke

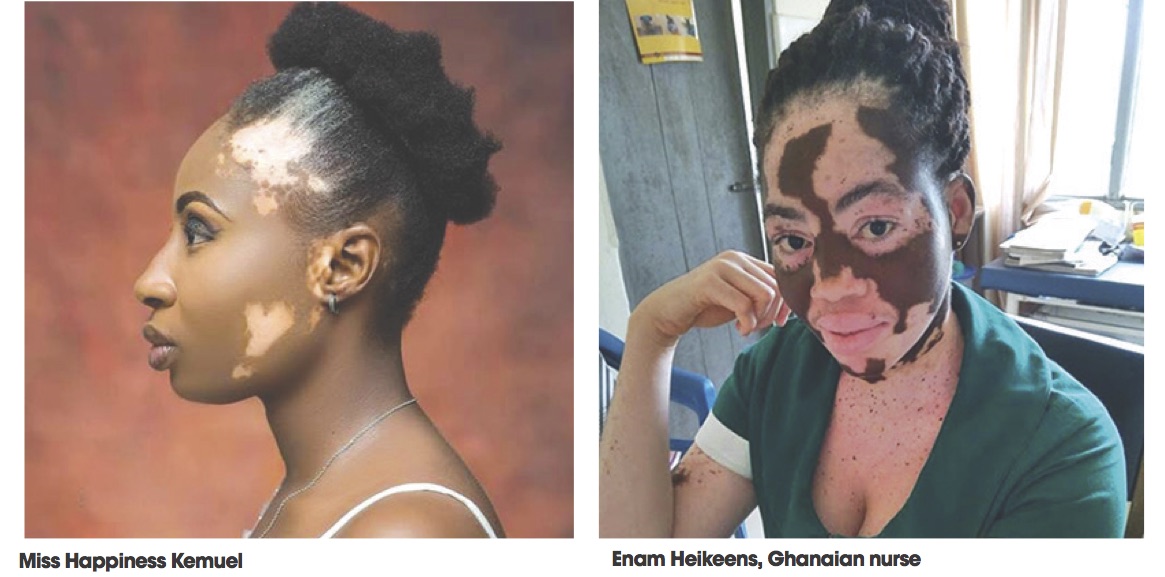

Rejection, discrimination and stigmatization have been the bitter experience of people living with vitiligo. The condition, which causes pale patches on the skin, can be psychologically and emotionally devastating, especially for people who have it on prominent parts of their body such as the face and neck.

According to a medical journal, “Vitiligo is an acquired pigmentry disorder of the skin and mucous membranes, which manifests as white macules and patches due to selective loss of melanocytes. Etiological hypotheses of vitiligo include genetic, immunological, neurohormonal, cytotoxic, biochemical, oxidative stress and newer theories of melanocytorrhagy and decreased melanocytes survival.

“There are several types of vitiligo which are usually diagnosed clinically and by using a Wood’s lamp; also, vitiligo may be associated with autoimmune diseases, audiological and ophthalmological findings or it can be a part of polyendocrinopathy syndromes.

“Several interventions are available for the treatment of vitiligo to stop disease progression and/or to attain repigmentation or even depigmentation. Vitiligo is the most common depigmentation disorder where the selective destruction of functioning melanocytes causes depigmentation of the skin, hair and mucosal surfaces. It affects approximately 0.5% to 1% of the population, with an average age of onset at about 24 years, its prevalence appears to be equal between men and women and there is no difference in the rate of occurrence according to skin type or race.”

Despite the fact that dermatologists and other social advocates have explained that the skin condition is not contagious, victims still suffer rejection from society.

Sharing her harrowing experience as one living with the condition, Ms. Happiness Kemuel, a graduate of business education from Rivers State University of Science and Technology, said: “I became conscious of vitiligo at the age of 26; it started with a part of my hair becoming grey in August 2019, and by January 2020 the other scars became noticeable.

“I felt my skin was irritated and booked an appointment with a dermatologist. I later saw the doctor in March and at that time the little patch had become very visible and I was told I had vitiligo. It was a bitter-sweet moment. I didn’t understand anything I was told.

“I had zero knowledge of vitiligo at that time. I had never heard of it. I battled depression. I stopped going to class. It was the first semester of my final year. I restricted myself from the outside world. People that knew me kept asking questions. Each time I tried to respond, I felt broken. It got so bad that I was afraid to look in the mirror.

“The dermatologist prescribed a topical cream that could be applied to avoid it spreading but I couldn’t find it in any of the pharmacies in Port Harcourt and Lagos. I browsed more about it and I got in-depth knowledge of using creams and oils with SPF that could help me protect my skin from the sun UV rays.

“The journey has been wonderful with beautiful compliments and a lot of admiration from people whenever they see my grey hair. This has boosted my self-confidence. I have felt renewed because I decided to accept the change I saw. I have been able to meet a lot of people who have been inspired by my story and the part I love so much is the exception I get from the crowd. I’m easily noticed in a large gathering because of my scars. My confidence level has risen.

“I visited a dermatologist at the initial stage but I was told it had no cure, and I should avoid exposing my skin to direct sunlight. I have experienced a lot of discrimination, especially from people who knew me before I had vitiligo. Someone told me in a public gathering that I had a terminal disease and death was knocking on my door, and this was a close friend. Other times, people are scared to touch me because they feel, once they do, they will contact vitiligo. I was told I had a contagious disease.

“I was backlashed by a close friend’s mother for having an affair with a married man and was poured acid, so I should avoid being friends with her daughter. Some people have also told me I have wronged people, that was why I was stricken with vitiligo.

“My advice to people who have vitiligo is that it is not a death sentence. It doesn’t make you less of who you are. Be confident in your skin. Embrace the uniqueness of your skin, because beauty is having a mix of qualities both inside and outside.

“Everyone is unique and having vitiligo should make you more confident. It is a trademark you have that most people don’t have.

“My expectations from the government are to provide a help centres for people with vitiligo like they have for other ailments. Provide us with basic facilities to help screen and examine people with vitiligo. We should have a registered body that other organizations can partner with and consciously aware people in our local communities and cities. Stop the discrimination, keep yourselves informed and, above all, show love to those living with vitiligo.”

Ogo Maduewesi, 44-year-old founder of a vitiligo awareness and support group, also shared her bitter experience.

She said: “I first noticed it in 2005. There was a possibility that it was there before, but that was when I first noticed it on the right side of my lip. I sought medical attention and the doctor told me it was a fungal growth and prescribed a drug, which I used for a month, but there was no improvement.

“Rather, I was still turning white. I went to the general hospital, close to Freedom Park, Lagos Island, but they had procedures, which I didn’t understand and I wasn’t able to meet a dermatologist. I talked to a family doctor over the phone but he didn’t really understand what I was saying. It was when he saw me that he finally told me it might be vitiligo. He encouraged me to go and read about it and seek help in the teaching hospital.”

After discovering what it was, it marked the beginning of Ogo’s woes. The white patches began spreading over her face, covering the better part of it. This made room for depression and self-pity as it was almost impossible for her to conceal her perceived imperfections.

“It was a whole trying day for me,” she continued. “I felt embarrassed and even embarrassed people too. There was a point, because people would always look at me and make me feel uncomfortable, I began to react. People started avoiding me; there was a feeling of rejection and I began to hide myself because I couldn’t even explain to anyone.”

But as time went on, Ogo decided to marry her fate and stomach whatever her condition threw at her.

“I told myself to accept it because I had no choice but to live with it. I got a message from my pastor in 2006; he said you allow people to treat you the way they treat you. I learnt that I was just allowing people to put me down and I decided to change and stay firm. So, I started working on my mind,” she said.

However, unlike Ogo who grew a thick skin and stood up to bullies, the case was different for 35-year-old Jude Aliyu, who started experiencing symptoms of vitiligo at the age of four. He was totally oblivious of how his skin rapidly changed.

He said: “The heartbreaking part about vitiligo is that it takes you unawares. My mother told me that she started noticing the patches on my skin at the age of four.

“She took me to different hospitals and was tired of taking me around after she had spent almost all her life’s savings and my father was not bothered because he knew the condition had no cure, but my mother was relentless, until the doctors told her that nothing could be done to change my skin to normal.

“It was when I became a teenager that I became conscious of the condition. First, it was my primary school teacher that made me know about it when he called me a leopard.

“I was confused and asked why he always called me the name of an animal. I reported my experience to my mother and it was at that point that she opened up and shared her ordeal and journey of how the condition began. Even my teacher didn’t have an idea of what the condition was. I guess he thought I was born that way.

“With the help of my mother, I learnt how to cope with the mockery and jest from my teacher, fellow pupils and others on my street. My mother helped me to build back my lost self-esteem, confidence and taught me how to have a sense of belonging in society.

“She taught me self-love and other things that helped boost my morale. Today, I have a help group where I encourage and sensitize people living with the same skin condition on how to accept themselves and not fall for rejection from society.”

From the experiences shared, the challenge of people living with vitiligo has always been mockery and the struggle of having a sense of belonging in society while pursuing their ambitions.

Responding to the claim that vitiligo was not contagious as expressed by other experts, Lagos-based dermatology consultant, Ayesha Akinkugbe, stressed that the condition, which may be difficult to treat, should not be a death sentence.

She said: “Vitiligo is a progressive disease, which is often difficult to treat. Responses to treatment may be slow and outcomes disappointing. But there are treatment options available. They include topical and systemic medications, light therapy (phototherapy) and surgical interventions.

“The major aim of treatment is to halt progression, prevent complications such as sunburn and ensure re-pigmentation of the white patches. The choice of treatment depends on the age of the affected person, extent of skin involvement, body part affected, progression of the disease and how it is affecting the quality of life.

“It is also important to address the psychological impact of the disease. Although vitiligo is a non-contagious disease and does not often lead to severe physical illness, it can cause significant psychological disturbance in the affected person. Many people with the disease suffer from shame, embarrassment, low self-esteem and social withdrawal. Psychosocial problems include poor body image, poor social relationships, matrimonial problems, social discrimination and stigma.”